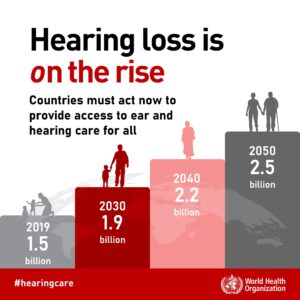

Hearing loss in young people aged 12-35 years is a growing issue worldwide [1]. Smart phones and iPads have come to dominate children’s lives and yet regulations limiting sound levels are not in place. Meanwhile, parents are struggling to regulate their children’s device usage. In 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated increase globally in the number of children with some level of hearing impairment (including mild and unilateral hearing loss) has been attributed to greater exposure to damaging levels of sound, largely through technological devices [2, 3].

Device use in children

Device use in children is surprisingly nuanced. Surveyed parents indicate their children are not just on TicToc and that devices fulfill a wide range of functions in children’s lives. For example, children use them to stay in touch with family and friends, but they are also used for more serious functions including assisting with their homework or learning something new through an educational website or app.

Although devices also lead to conflict surrounding bedtime and mealtimes, parents are cautiously optimistic about their usage and feel that their benefits for pursuing hobbies and interests, expressing themselves, developing relationships and learning social and emotional skills seem to outweigh more negative aspects. [4]

As such, parents need to be more concerned about how they will be used rather than whether they should be used at all. Instilling”digital literacy” skills will be essential for children to get the most out of their devices with as little harm as possible.

However, this means that devices are here to stay. And as such, the predictions made by WHO of dangers for the hearing of young people persist.

What are the risks?

A central effect hearing loss is the way it impacts on communication. These effects are largely due to the barrier that spoken and written language represent to children with hearing loss.

When the brain is exposed to sound signals that are unclear, it is unable to form strong neural representations of those sounds. Without robust sound representations, a child with hearing loss struggles to make sense of the words they are hearing. This is especially true when the sounds are presented in challenging situations, such as when many people talk simultaneously or when there is background noise. [5]

This trickles down to all levels of interaction, from the community down to the family unit. Compiled with healthcare costs is the inability to truly participate in society on an equal basis. Consequently, a persistent influence on individuals’ working lives, relationships and quality of life is felt throughout the lifespan.

Poor acoustic conditions compound the effects of hearing loss

This makes it even more essential that sound environments are optimized for children with both typical hearing but also those with special listening needs. Children with hearing loss can’t cope as well with speech when there are unwanted sounds, but poor acoustics compounds the situation.

WHO’s “World Report on Hearing” from 2021 [6] states that: “Good acoustics are critical to learning for young children who have less well-developed phonological knowledge of the world than adults, and are thus less able to reconstruct degraded speech information. Unsuitable acoustics present an even greater challenge for children with hearing loss or learning problems.”

Having a good acoustic environment in the classroom is essential because more children with hearing loss than ever go to mainstream schools. For example, as of 2019, 78% of children with hearing loss are mainstreamed in the UK [7]. And the research indicates that poorer classroom acoustic conditions disproportionately affect children with hearing loss (for a review, see [8]).

The context in which children are learning is also changing, as pedagogical styles shift and the classroom structure needs to be more adaptable. Many countries are shifting towards more open-plan classroom designs in an effort to keep up with pedagogical trends, but these environments are not necessarily suited to mainstreaming.

WHO states that: “Open plan learning is becoming increasingly popular in some settings to enhance flexible teaching and learning practices; however, acoustic modifications to support this have often been overlooked, leading to poor perception of auditory information.”

The end result is a marked effect on children’s overall academic performance. They pass through the educational system more slowly, show a greater incidence of dropping out from school and are less likely to go to university than children with typical hearing [9, 10].

What can we do about it?

The Canadian Hard of Hearing Association has developed a method of managing noise, reverberation and speaker-listener distances in classrooms for persons with hearing loss. Their approach is informed by Universal Design, which aims to unlock the sound environment for people from across the spectrum of auditory ability. They recommend noise be managed in acoustic design through five strategies referred to as “RAMPS” [11]:

- Reduce Noise.

- Amplify teacher and student voices

- Manage noise, reverberation and distance (reducing background noise by closing doors, turning machines off, closing windows and landscaping)

- Parents and professionals working together (special education advisory committees and parents advocate for acoustical upgrades and help raise funds)

- Student strategies (appropriate seating, peer help with P.A. announcements, print versions of material provided in an audio format)

Acoustic recommendations for children with hearing loss

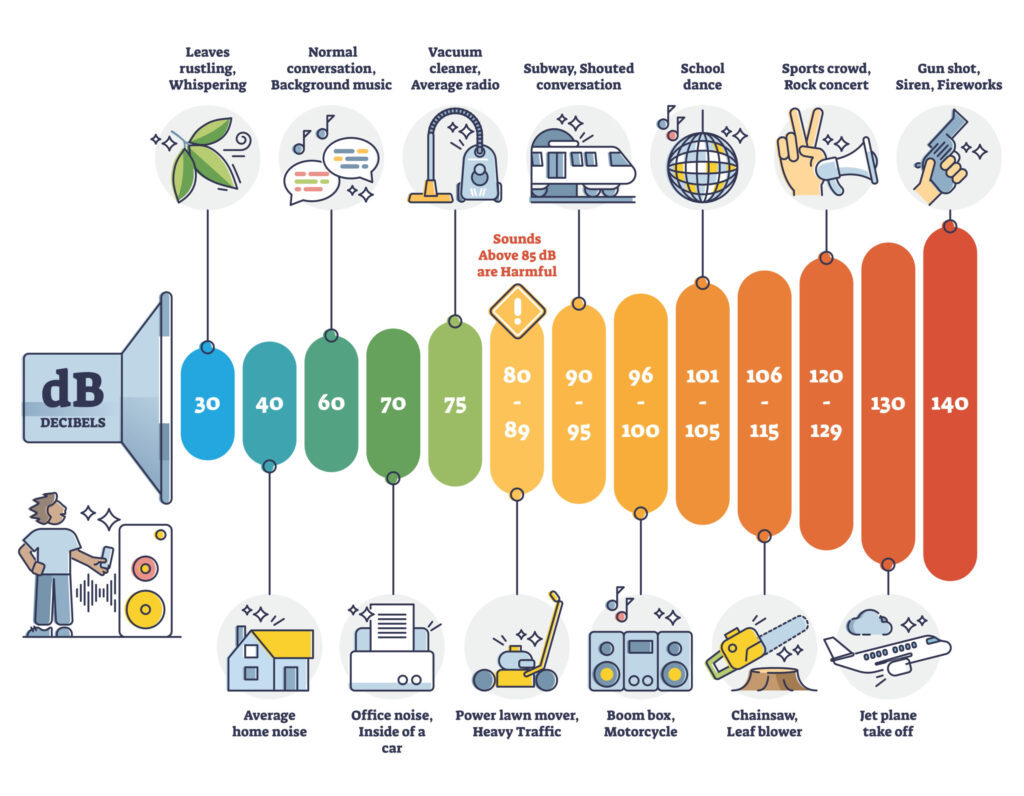

Acoustic guidelines for children with special hearing needs can be used as a guide for designing inclusive classrooms. WHO [12] recommend that in order to hear voices speaking normal conversational speech level (approximately 50 dB(A)), a signal-to-noise ratio of 15 dB is recommended. However, the BATOD (British Association for Teachers of the Deaf) guidelines recommend up to a 20 dB signal-to-noise ratio at 125-750 Hz [13].

Background noise should be as low as possible, especially in educational contexts in which language is prioritized, but 35 dB(A) would be required in order for the recommended signal-to-noise ratio in relation to normal conversational speech to be maintained. Reverberation times of less than or equal to 0.4 seconds in the 125 Hz to 4 kHz range are recommended by the British standard for education [14].

Prevention is better than a cure

WHO have also created a standard for safe listening devices and systems (see [15]) which aims to reduce the risk of hearing loss. This standard will require the device to contain software that will record sound exposure and inform the user of dangerous levels as well. For children, the recommendation is 75 dB for a maximum of 40 hours per week. The standard will require software to provide volume-limiting options. This will include the option to have “parental volume control” that is password protected.

However, it is unlikely that this wave of hearing loss can be avoided unless a huge effort is made to reduce children’s exposure to damaging sounds in both educational and recreational settings.

Sources

[1] World Health Organization. (2021). World report on hearing.

[2] World Health Organization. (2018). Hearing loss due to recreational exposure to loud sounds: A review.

[3] International Telecommunication Union. (2015). ITU Guidelines for safe listening stystems/devices.

[4] Livingstone, S., Blum-Ross, A., Pavlick, J., & Ólafsson, K. (2018). In the digital home, how do parents support their children and who supports them?.

[5] Crandell CC, Smaldino JJ. (2000). Classroom acoustics for children with normal hearing and with hearing impairment. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 31(4):362–70.

[6] World Health Organization. (2021). World report on hearing.

[7] Consortium for Research on Deaf Education (2019). 2019 UK-wide summary: CRIDE report on 2018/2019 survey on educational provision for deaf children.

[8] Crandell, C. C., & Smaldino, J. J. (2000). Classroom acoustics for children with normal hearing and with hearing impairment. Language, speech, and hearing services in schools, 31(4), 362-370.

[9] Idstad M, Engdahl B. (2019). Childhood sensorineural hearing loss and educational attainment in adulthood: results from the HUNT study. Ear Hear. 40(6): 1359–67.

[10] Järvelin MR, Mäki-Torkko E, Sorri MJ, Rantakallio PT. (1997). Effect of hearing impairment on educational outcomes and employment up to the age of 25 years in northern Finland. Br J Audiol. 31(3):165–75.

[11] Canadian Hard of Hearing Assocaition, 2008. Universal Design and Barrier-Free Access: Guidelines for Persons with Hearing Loss.

[12] Berglund, B., Lindvall, T., Schwela, D.H. and World Health Organization. (1999). Guidelines for community noise.

[13] Building bulletin 93. (2015). Acoustic design of schools: performance standards.

[14] British Association for Teachers of the Deaf. (2001). Classroom Acoustics – recommended standards.

[14] WHO, Safe listening devices and systems: a WHO-ITU standard.