The hospital soundscapes

“The soundscape of the average modern hospital is a cacophony of overlapping beeps, blats, and pings from monitors, roaring ventilation systems, raucous bursts of conversation from visitors, patients and the nursing station, carts rumbling down hallways, televisions, phones. Sleep, essential to the healing process, is available primarily through medications. Even medicated sleep can be elusive, however, when mechanical alarms sound in the patient’s room at an average of six times per hour, signaling nurses and technicians to perform tests and administer medications as well as alerting the nursing station to emergencies (Görges et al. 2009). While the procedures are necessary, the use of auditory signals can be counterproductive: sleep disturbance for patients is echoed by stress for staff, who are expected to respond immediately to alarms and call buttons even when there are not enough of them available to do so.” (Epstein 2020, p. 238-9)

This passage, from a chapter in my recently published book Sound and Noise: A Listener’s Guide to Everyday Life — an interdisciplinary examination of how sound influences human health and culture — introduces the issue of noise in hospitals as a threat to healing. Since so many articles in Acoustic Bulletin focus on the same subject, it seems a good way to begin my guest blog.

This passage, from a chapter in my recently published book Sound and Noise: A Listener’s Guide to Everyday Life — an interdisciplinary examination of how sound influences human health and culture — introduces the issue of noise in hospitals as a threat to healing. Since so many articles in Acoustic Bulletin focus on the same subject, it seems a good way to begin my guest blog.

One Bulletin entry in May 2020 even refers to Florence Nightingale’s criticism, in 1859, of noise as “the cruelest abuse of care” to which patients could be subjected. Noise is still an irritant in hospitals today. Anesthetics, antibiotics, and pain medications eliminate most of the screams and groans Nightingale would have heard from wounded soldiers, but nurses and patients now have to contend with annoyance and interrupted sleep caused by mechanical infrastructure and monitoring devices.

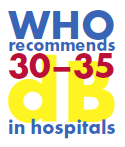

Today, most advanced modern hospitals have averaged noise levels at least double the 30-35 decibels recommended by the World Health Organization. Averaged levels in North American hospitals were reported in 2012 to be 72 dBA in the daytime, and 60 dBA – equivalent to a busy office — at night (Pope 2012). Given the proliferation of machinery to monitor patient conditions since then, averages may well be louder by now. Levels in many developing countries are far louder because of poverty, lack of access to advances in soundproofing materials, or location in conflict zones.

Why so much noise?

One of the contributing factors is technology: the essential machines and measurement devices that monitor recovering patients and keep ICU patients alive by alerting hospital staff to changes in respiration, heart rhythm, blood pressure, and function of organs. Another, of course, is building and infrastructure design. A third is the activity of staff: their footfalls, interactions with infrastructure (doors, carts, equipment), and their voices in conversation. In psychiatric units, the combination of HVAC, machinery, staff activity, and patient vocalization can produce average levels of 76 dBA, equivalent to heavy traffic, with 90-decibel peaks easily capable of traumatizing noise-sensitive patients (Holmberg and Coon 1999).

One of the contributing factors is technology: the essential machines and measurement devices that monitor recovering patients and keep ICU patients alive by alerting hospital staff to changes in respiration, heart rhythm, blood pressure, and function of organs. Another, of course, is building and infrastructure design. A third is the activity of staff: their footfalls, interactions with infrastructure (doors, carts, equipment), and their voices in conversation. In psychiatric units, the combination of HVAC, machinery, staff activity, and patient vocalization can produce average levels of 76 dBA, equivalent to heavy traffic, with 90-decibel peaks easily capable of traumatizing noise-sensitive patients (Holmberg and Coon 1999).

The routines of hospital procedures are another source. One study conducted in India reported on efforts to reduce noise in a newborn ICU. Rubber pads were attached to the feet of furniture, alarm volume was reduced, metal trays were handled gently to reduce clashing, and the staff was reminded to speak softly. The average sound level was reduced to 60 dBA, not even close to the goal of 50 (Ramesh et al. 2009).

Communication in operating rooms is crucial to safety, but noise intrudes even during surgery. A survey of medical literature published in 2014 showed that machine noise and irrelevant conversation could distract surgeons. That wasn’t surprising to the researchers, but they also found that the hearing acuity of anaesthesiologists as well as patients could be damaged during long procedures involving bone saws and other mechanical devices (Katz 2014).

The use of music can be effective for reducing patient anxiety before surgery, but it can function as noise during surgeries if played loudly enough to be heard over HVAC: one UK study found that repetition of instructions was five times more likely to be needed when music was present (Weldon et al. 2015). Even the storage facilities in operating rooms can pose a noise hazard: the sharply rattling doors of old metal cabinets were mentioned by one cardiac surgeon as having the potential to cause a fatality through a startle response (Dubbs 2004).

With so many sources of noise, how might hospitals ensure healing hospital soundscapes?

The obvious solutions – better insulation, quieter machinery, staff training, better building design – are not always effective or affordable, but some innovative practices are showing promise. One is designated quiet times during the day when visitors are prohibited and patients are encouraged to catch up on sleep (Gardner et al. 2009, Dennis et al. 2010). For some patients, inexpensive earplugs may be helpful (Wallace et al. 1999). If sudden noises interrupt sleep at night, a white noise machine can override the startle effect by reducing the contrast between the ambient decibel level and the foreground noises. HVAC noise, often a problem, might be an advantage in this case since it provides a steady background that reduces the significance of other sounds, as long as it isn’t loud enough to prevent sleep.

Ultimately, the best solutions are related to good design and knowledge of the issues. Since the main obstacle to implementing good design is cost, hospital administrators should be made aware of the importance of providing quality materials and techniques for reducing noise. Hospital staff will benefit from training in best practices, as well as reminders to avoid loud speech when interacting with patients and each other in non-emergency situations. If all else fails, keep a supply of comfortable earplugs at the nursing station.

Ultimately, the best solutions are related to good design and knowledge of the issues. Since the main obstacle to implementing good design is cost, hospital administrators should be made aware of the importance of providing quality materials and techniques for reducing noise. Hospital staff will benefit from training in best practices, as well as reminders to avoid loud speech when interacting with patients and each other in non-emergency situations. If all else fails, keep a supply of comfortable earplugs at the nursing station.

About the guest blogger

Name: Marcia Jenneth Epstein, Ph.D.

Location: Calgary, Alberta; Canada

Company: University of Calgary – Department of Communications, Media and Film.

Where do you go to find peace? Mountain hiking (the Rockies are an hour away) and local walking trails.

Favorite sound? Lots of them, e.g. Renaissance and Baroque music (I’m a trained choir singer, and being inside live polyphony is a natural high), birdsong, cats purring, waterfalls, and rain.

How did you end up working with acoustics? I’m a musicologist who wandered into acoustic ecology & soundscape studies because it’s new and exciting.

What acoustics-related challenges do you face? Teaching in poorly-designed classrooms!

What is it like to work with room acoustics in your country? Canada isn’t as well aware of the issues as Europe. I don’t work directly on room acoustics but have colleagues who do; they report that new projects here are generally well-planned, but remodeling to improve acoustics in older buildings is not always done because of costs.

What trends do you see in room acoustics? I’m hoping that the post-pandemic recovery will encourage better attention to sound in communication.

________________________________________________________________

Sources:

Dennis, Christina M., Robert Lee, Elizabeth K. Woodard, Jeffrey J. Szalaj, and Catrice A. Walker. 2010. “Benefits of Quiet Time for Neuro-Intensive Care Patients.” Journal of Neuroscience Nursing 42, no. 4: 217–24. doi:10.1097/JNN.0b013e3181e26c20.

Dubbs, Dana. 2004. “Sound Effects: Design and Operations Solutions to Hospital Noise.” Health Facilities Management 17, no. 9: 14–18. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15478713.

Gardner, Glenn, Christine Collins, Sonya Osborne, Amanda Henderson, and Misha Eastwood. 2009. “Creating a Therapeutic Environment: A Non-Randomised Controlled Trial of a Quiet Time Intervention for Patients in Acute Care.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 46, no. 6: 778–86. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.12.009.

Görges, Matthias, Boaz A. Markewitz, and Dwayne R. Westenskow. 2009. “Improving Alarm Performance in the Medical Intensive Care Unit using Delays and Clinical Context.” Anesthesia & Analgesia 108, no. 5: 1546–52. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e31819bdfbb.

Holmberg, Sharon K., and Sharon Coon. 1999. “Ambient Sound Levels in a State Psychiatric Hospital.” Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 13, no. 3: 117–26. doi:10.1016/S0883-9417(99)80042-9.

Katz, Jonathan. 2014. “Noise in the Operating Room.” Anesthesiology 121, no. 4: 894–8. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000000319.

Pope, D. “Decibel Levels and Noise Generators on Four Medical/Surgical Nursing Units.” 2010. Journal of Clinical Nursing 19, no. 17–18: 2463–70. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03263.x.

Ramesh, A., P.N. Suman Rao, G. Sandeep, M. Nagapoornima, V. Srilakshmi, M. Dominic, and Swarnarekha. 2009. “Efficacy of a Low-Cost Protocol in Reducing Noise Levels in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit.” The Indian Journal of Pediatrics 76, no. 5: 475–8. doi:10.1007/s12098-009-0066-5.

Wallace, Carrie J., Judith Robins, Lynn S. Alvord, and James M. Walker. 1999. “The Effect of Earplugs on Sleep Measures during Exposure to Simulated Intensive Care Unit Noise.” American Journal of Critical Care 8, no. 4: 210–19. http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/content/8/4/210.abstract.

Weldon, Sharon-Marie, Terhi Korkiakangas, Jeff Bezemer, and Roger Kneebone. 2015. “Music and Communication in the Operating Theatre.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 71, no. 12: 2763–74. doi:10.1111/jan.12744.