Jack-Harvie Clark demonstrated that the perception of the acoustic environment is influenced by numerous factors. Working on room acoustics alone can help reduce annoyance caused by noise. Achieving acoustic satisfaction necessitates considering many additional factors that extend beyond room acoustics.

Dissatisfaction with noise levels kills productivity

Jack Harvie-Clark outlined at the beginning of this talk a strong link, supported by studies, between dissatisfaction with noise levels and self-evaluated productivity. Meanwhile, a Leesman survey showed that satisfaction with office acoustics has not significantly changed over the decade. Jack’s conclusion was that “offices fail”.

The Impact of Sense of Control

Jack shared his findings from measurements he conducted in a client’s office. Sound assesment was carried out twice, before and after transitioning to an activity-based workplace (ABW). He measured parameters according to ISO 3382-3 and ISO 22955 and also assessed liveliness. Surprisingly, acoustic parameters in both unoccupied and occupied spaces remained very similar before and after the transition. However, satisfaction with acoustics and lighting increased in the ABW setting, despite no change in the lighting itself. What changed was the individual sense of control. Employees in the ABW setting had access to protected, quiet areas they could choose to work in. This sense of control, often overlooked by acousticians, may contribute to the variability in data aiming to show connections between acoustic parameters and acoustic satisfaction. This concept also extends to the radius of distraction, a parameter closely linked to the perception of the office environment. Jack suggested the need for a new model or framework to describe our response to sound.

Soundscape of the Office: Beyond Acoustic Factors

Non-acoustic factors significantly influence our experience of sound. Individual factors such as noise tolerance, coping abilities, perceived fairness, and perceived control play a role. Environmental factors, often termed visual modifiers, also matter. For example, people in traffic are less bothered by noise when surrounded by greenery. Personality traits also play a significant role. Extroverts are more content with sound levels at both assigned and non-assigned desks compared to introverts. The data suggests that both extroverts and introverts are less satisfied with allocated desks compared to non-allocated ones. It highlights the importance of a sense of control. Studies also demonstrate links between individual needs for privacy, the perceived fit of the work setting with the activity, environmental satisfaction, and overall performance.

Managing Workplace Change

People working in cellular offices often prefer that setting. After being tranistioned to an Activity-Based Workplace (ABW) setting, they seldom want to return. It is the change itself that instills fear in employees, emphasizing the need for well-planned change management processes. The expectations created during the transition can significantly impact the comfort employees feel in the new setting. Jack questioned why these psychological factors aren’t considered in acoustic design, even though they affect the acoustic outcomes.

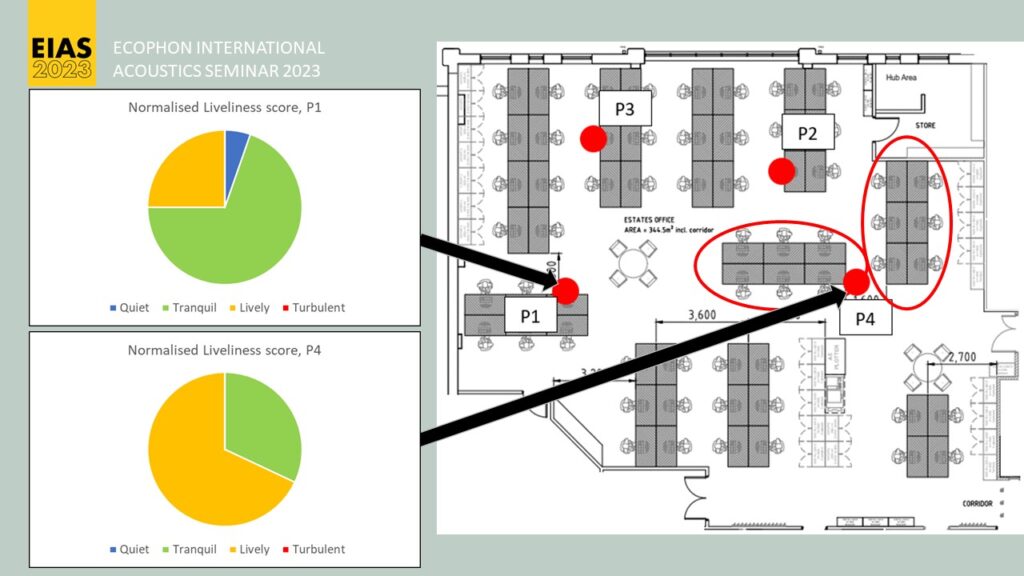

Acoustic Space Planning

Jack showed an example of an office that clearly illustrated the importance of acoustic space planning. He conducted acoustic measurements in an office, where most of the space teruned out to be notably tranquil. There was only one area where many conversations took place. The focus was on providing these individuals with a protected zone. Jack emphasized, “The office is a tool that we provide to the users. They work with it, and then we can help them learn how to use it better. It’s a process of learning”.

Changing the narrative

According to Jack, we must shift our mindset when dealing with office acoustics. “We need to change the narrative to focus on acoustic satisfaction. Acoustic satisfaction doesn’t exist within the room. It only exists in people’s minds,” he concluded.